Our History

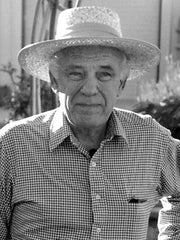

Charles Walters, Acres U.S.A. founder

“I didn’t have the money to buy a paper, so I started one,” said Charles Walters in 1995, remembering the origins of Acres U.S.A. for the journal’s 25th anniversary issue. “I wanted the freedom that went with making my own decisions without the blessings of higher approved authority.”

“I didn’t have the money to buy a paper, so I started one,” said Charles Walters in 1995, remembering the origins of Acres U.S.A. for the journal’s 25th anniversary issue. “I wanted the freedom that went with making my own decisions without the blessings of higher approved authority.”

A confirmed maverick in his early 40s, Walters had more than a passing acquaintance with the havoc unleashed by higher authorities and historical forces. The son of a poor Kansas farmer, his childhood was marked first by the Dust Bowl, then by the Great Depression. He came of age doing military service in the waning days of World War II, and earned a master’s degree in economics on the G.I. Bill. As he made his way in several major urban centers, finally settling in Kansas City, Missouri, with his wife, Ann, Charles Walters never lost his connection to the world of farming. It was not lost on him when a flood of corporate money pushed the American farmer into an expensive new dependence on supercharged fertilizers and powerful new pesticides — about which little was known.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a devastating attack on DDT and other agricultural chemicals that shocked the world, became a cornerstone of the unique point of view Walters would bring to Acres U.S.A. Equally crucial was his experience as editor for the National Farmer’s Organization (NFO), a group dedicated to the idea of using collective bargaining to obtain a better deal for the family farmer.

Assembling NFO’s house journal every month and working in his spare time on Unforgiven, a book about visionary farm economist Carl Wilken, Walters made a breakthrough. He realized how the methodical cheating of small farmers and the enforced swing toward chemical agriculture were gears in the same machine, working in tandem to transform the countryside. And not for the better. Corporate power and public policy were colluding in the destruction of the family farm, and the process of annihilation was gathering speed.

After faltering leadership hobbled NFO, Walters knew he had to fight the good fight on his own terms. Acres U.S.A. was his base camp, and while he struggled to keep it afloat in the early years, the journal immediately attracted a throng of fascinating figures. It seemed there were other mavericks out there who needed a forum, and they came out of the woodwork. Soil scientists, farm policy experts, economic thinkers, insect researchers, philosophers of the land — Walters met many of them through Acres U.S.A., interviewing them, commissioning articles by them and inviting them to speak at the annual conference he began in 1975.

Rescuing Lost Knowledge

Perhaps the most important was Dr. William A. Albrecht, a University of Missouri professor whose low profile obscured decades of brilliant work in soil science. Albrecht’s papers, which Walters rescued from the historical dustbin and published in several volumes, provided a rock-solid foundation for this new, scientific approach to organic farming that Acres U.S.A. liked to call eco-agriculture.

A dynamo who packed a lot of productive effort into a day, Walters completed over a dozen books while he edited Acres U.S.A., writing most of them himself and co-authoring several others. He wrote a good chunk of every issue as well, seldom attaching his byline to many of the pieces. Loyal readers recognized his voice anyway.

A tireless traveler, Walters journeyed to Egypt, Cuba, Australia and Brazil (among others), always returning with long, insightful articles about the rural culture and agricultural practices he found and the people he met. His trip to China in 1976 resulted in a series of articles that proved a huge hit with readers. The People’s Republic was not yet open to tourists, and Walters’ pieces offered a fascinating look at a still mysterious society.

By the time his health forced him to cede the day-to-day job of editor-publisher to his son Fred, Charles Walters could look back on a quarter century in which he helped change the world. The other national journals devoted to organic farming were no longer around, while national demand for wholesome food now supported thriving supermarket chains. Demand for produce free of toxic residues was leaping upward every year. As a small army of brave souls, deemed “statistically insignificant” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, began the decades of work it will take to rescue the family farm from oblivion, many of them cited Acres U.S.A. as the operating manual they could not do without.

Charles Walters contributed articles and essays to the journal he founded until his death in January 2009.

Share: